In turbulent and fast paced times, how does one establish a name for oneself as an inventor or scientist, particularly in the field of engineering? Where would be the best place to publicise a discovery, claim an invention or announce the opening of a new field of research? Such questions are asked today and were asked over two hundred years ago too.

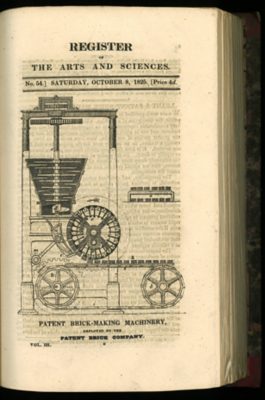

For an inventor working in the 1820s one answer could have been to take out a patent or caveat. However, for many who considered themselves the next Watt or Arkwright, this was not enough, as it was only with investment that an idea on paper could have the hope of being translated into commercial success. As such, the early decades of the 19th century saw the founding of new magazines to drum up the attention that brought financing. Among these publications, all conveniently printed in coat pocket-sized octavo, were “Mechanics Magazine” (Iron Library Per 254) and the “Register of The Arts and Sciences”. The complete run of the latter of these, published biweekly from 1823 to 1827, is now to be found in the collection of the Iron Library.

The convenience of magazines of its type for advertising new ideas from established as well as aspiring industrialists, meant that in very little time they had become part of the required reading for all who held influence over business and industry in what statesman Benjamin Disraeli later termed the “Workshop of the World”. Indeed, while he was visiting London in 1827, GF’s founder Johann Conrad Fischer called into a bookshop on Paternoster Row and bought himself a stack of issues of the Register too.

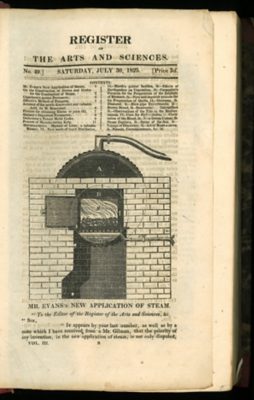

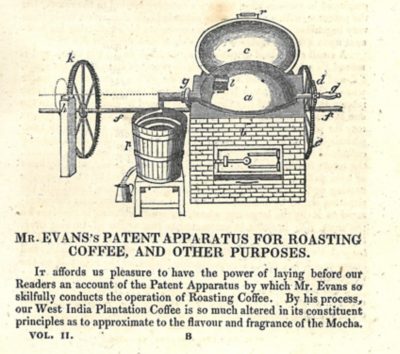

The Register was dedicated to the specifications of patented inventions, technical descriptions of engineering innovations, and commentaries upon the practical scientific applications of discoveries amidst the unprecedented manufacturing feats of the Industrial Revolution. Much space is given to the production of more efficient steam engines, with numerous contributors clearly seeking to capitalise on the still emergent technology to make their fortune. Notable amongst these is the earliest published description of Brunel's Patent Steam Engine which Fischer observed in operation at the Thames tunnel works at Rotherhithe.

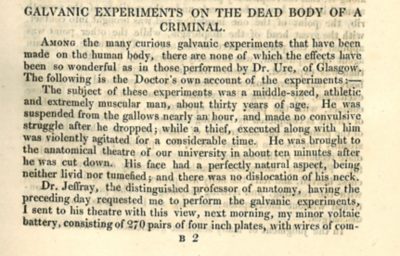

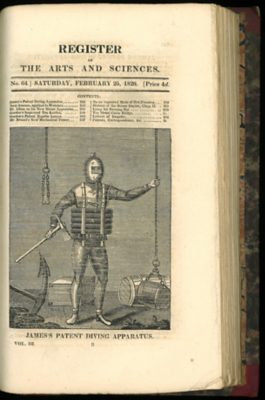

The publication’s interests were by no means limited to steam engines and their components, however. Alongside suggestions for the improvement of railway infrastructure, urban planning, sewers, and chemical apparatus are to be found tracts against the treadmill as physical punishment, designs for a diving suit, reports on experiments for ensuring the vivid greenness of vegetables, suggestions on how best to extinguish a burning dress, a patent for an improved ship’s rudder, and speculations on the economy of a railway powered by sail. There is even a chilling laboratory report on galvanic experiments on the body of a criminal by chemist Andrew Ure that is reminiscent of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which had been published in 1818.

The Register’s plurality of interests at a time when other journals were specialising, means that it counts among the last of the publications targeted at the polymaths who had dominated and shaped science and technology in the preceding century. It highlights the tremendous breadth of the Industrial Revolution as an epoch of multiple revolutions in manifold fields, many of them new, and a time since which the pace of technology’s change and development has never slowed.