Joachim von Sternberg: Reise nach den ungarischen Bergstädten Schemnitz, Neusol, Schmölnitz, dem Karpathengebirg und Pest im Jahre 1807. (Wien 1808).

published April 2019

The favorite book of Mariann Juha

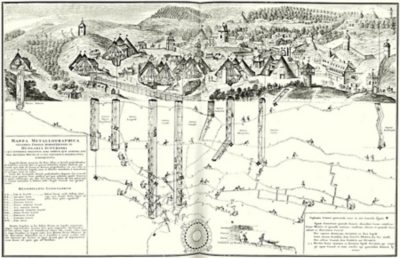

Mariann Juha worked in the Iron Library for two weeks as a scholar-in-residence studying literature relating to mining history. Her project "Mining Traditions. The Intangible Legacy of Mining" deals with the question of what links the populations of Europe's former mining centers. The starting point for her research is the former silver-mining town Banská Štiavnica (Schemnitz in German). During her research she came across her favorite book, a fascinating travelogue.

&crop=(126,76,588,363))